Vision involves the light sensitive photoreceptors cells in the retina absorbing light, a process which naturally creates waste products. Under normal circumstances, these waste products are broken down by the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and transported away from the eye by the blood supply. This process becomes less efficient with age.

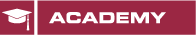

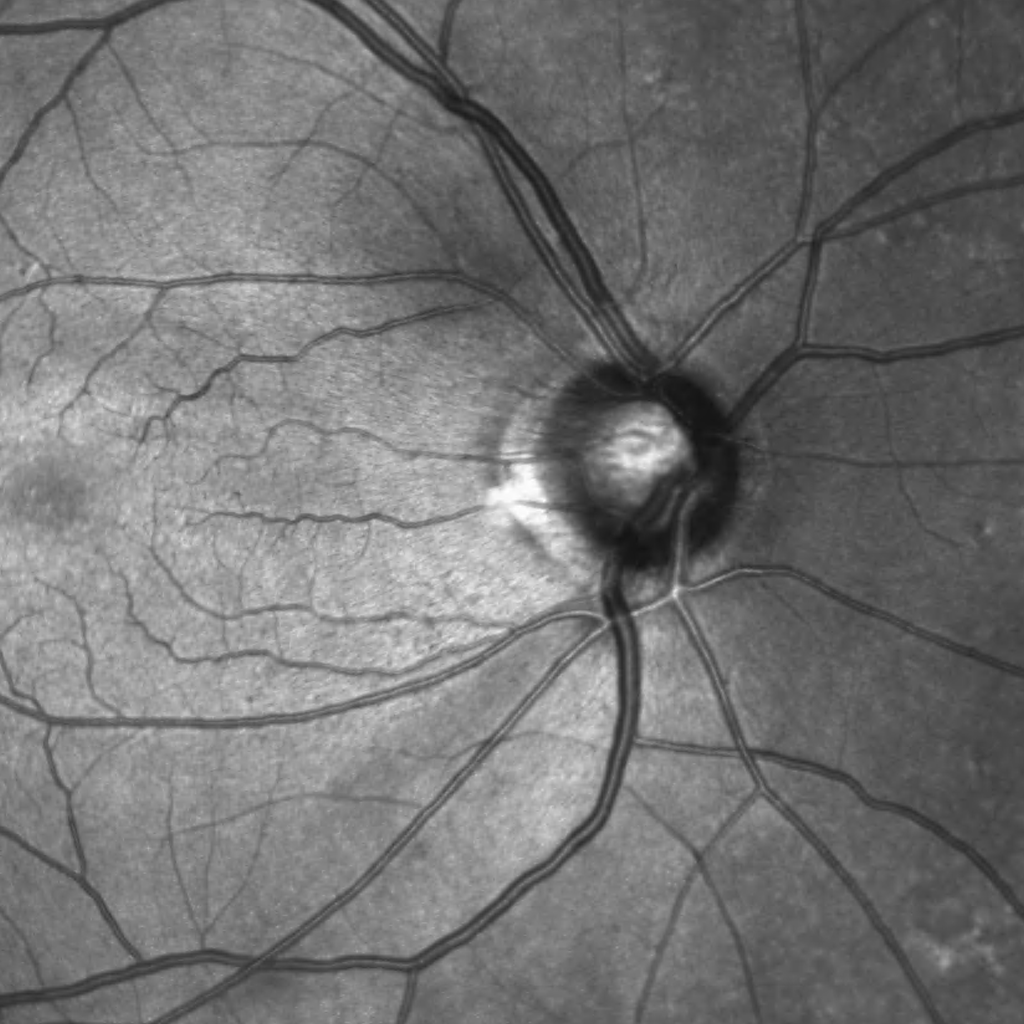

In dry AMD, these degraded products cannot be removed sufficiently, leading to a gradual build-up of waste products, so-called drusen, beneath the RPE cell layer. If the number and size of the drusen increase significantly over time, some RPE cells become damaged and may die. The photoreceptor cells above can no longer be adequately supplied with nutrients and can also die, leading to vision loss in this area. In its late stage, dry AMD is referred to as Geographic Atrophy.

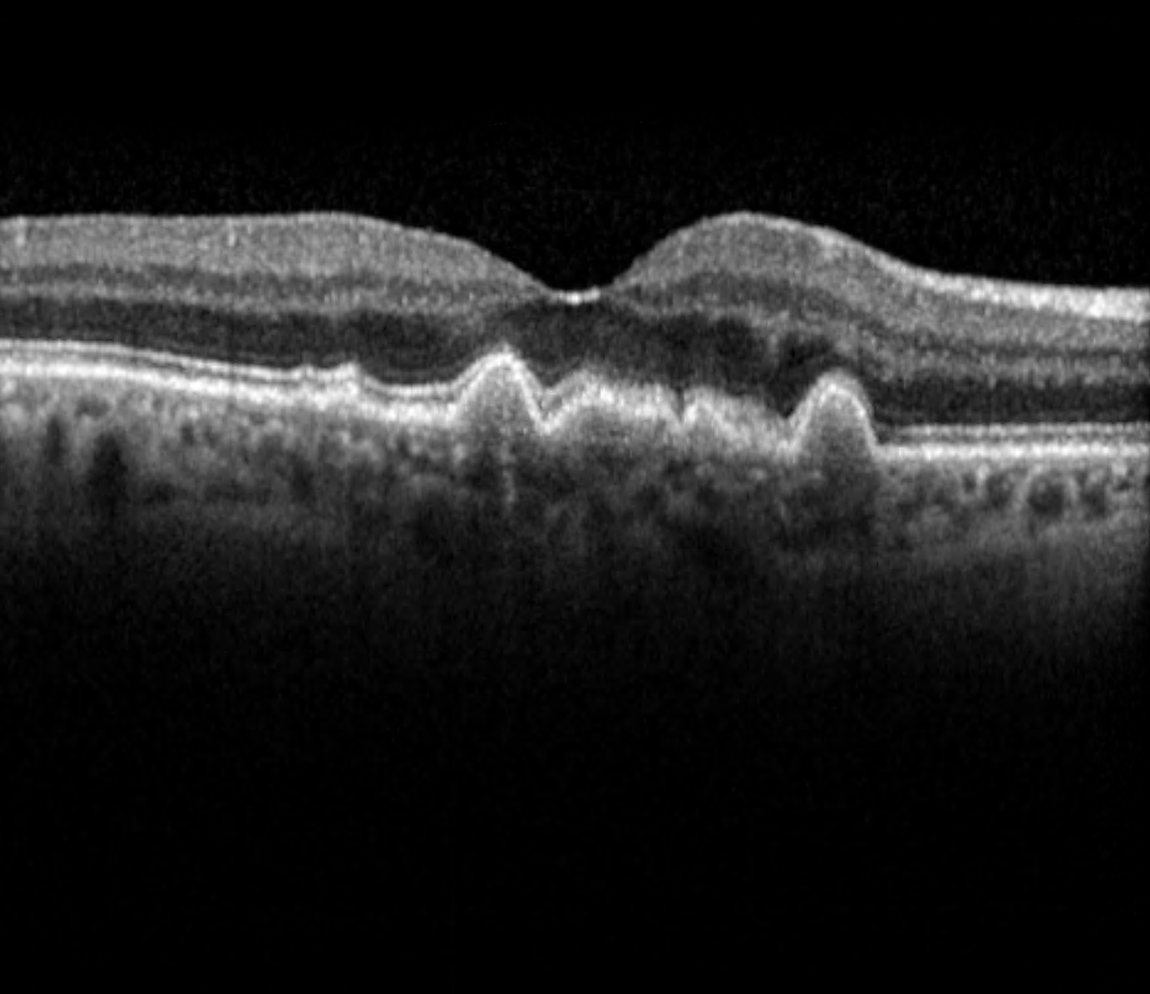

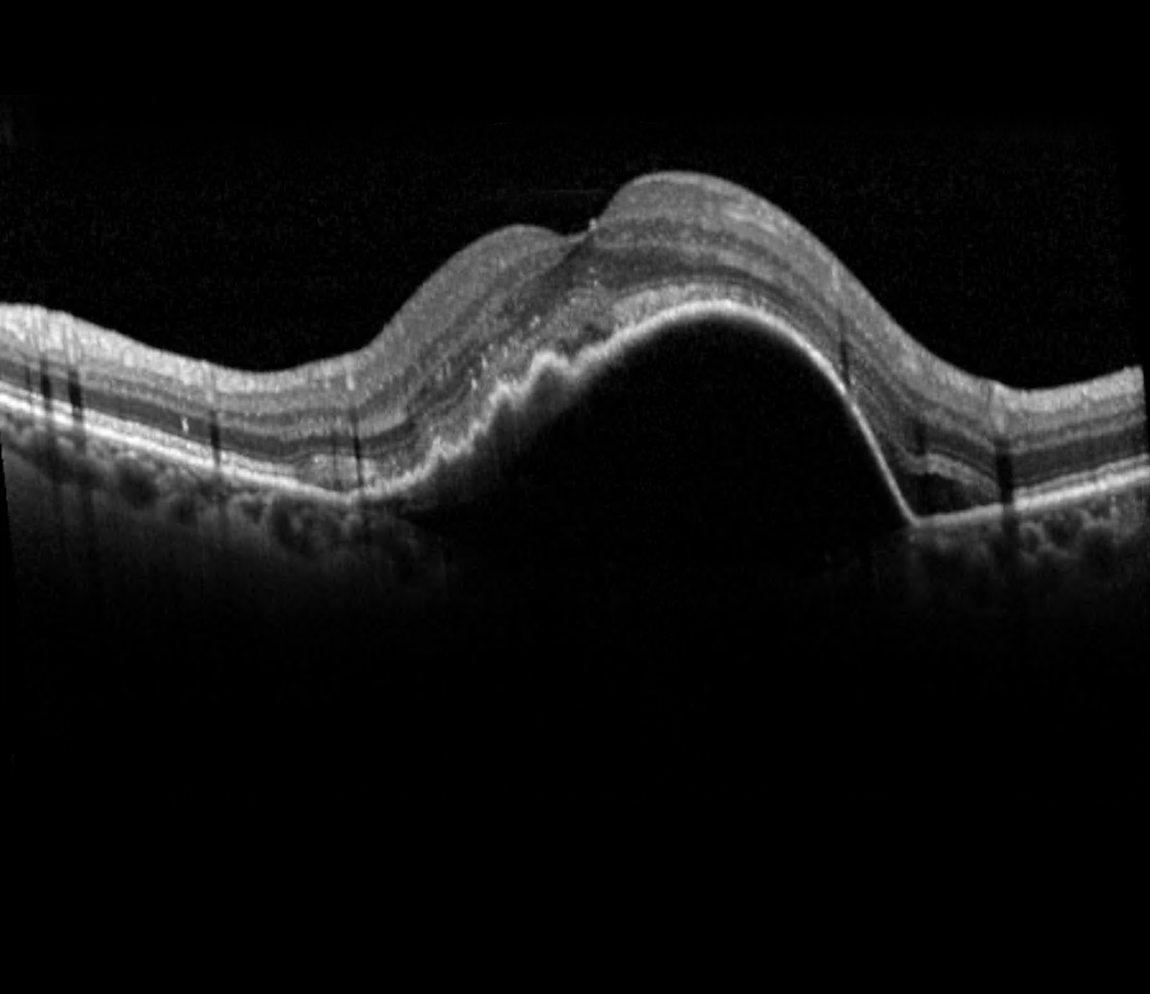

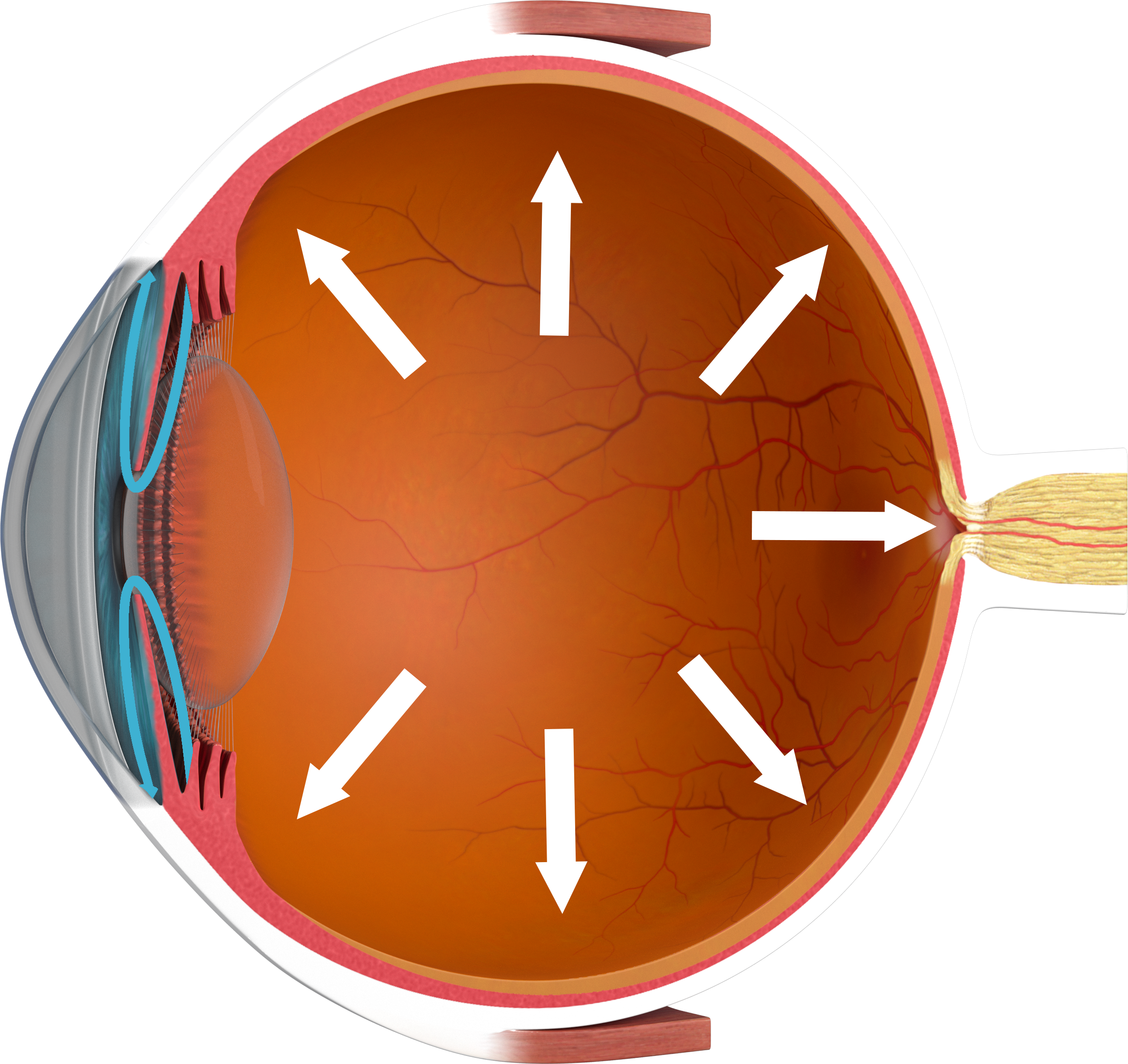

In wet AMD, the build-up of drusen and degeneration of the RPE has started to impair the supply of oxygen to the photoreceptor cells. In response, the retina releases the signaling molecule VEGF, to encourage the formation of new, blood vessels within the retina. However, such new vessels are structurally immature with fragile vessel walls that can suddenly leak fluid/blood. The fluid forms little cystoid spaces within or beneath the retina, distorting vision. Left untreated, permanent vision loss may occur.

The risk of AMD increases with age, especially after 70, and is influenced by family history and unhealthy lifestyle factors such as smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity, high blood pressure, obesity, and diabetes.

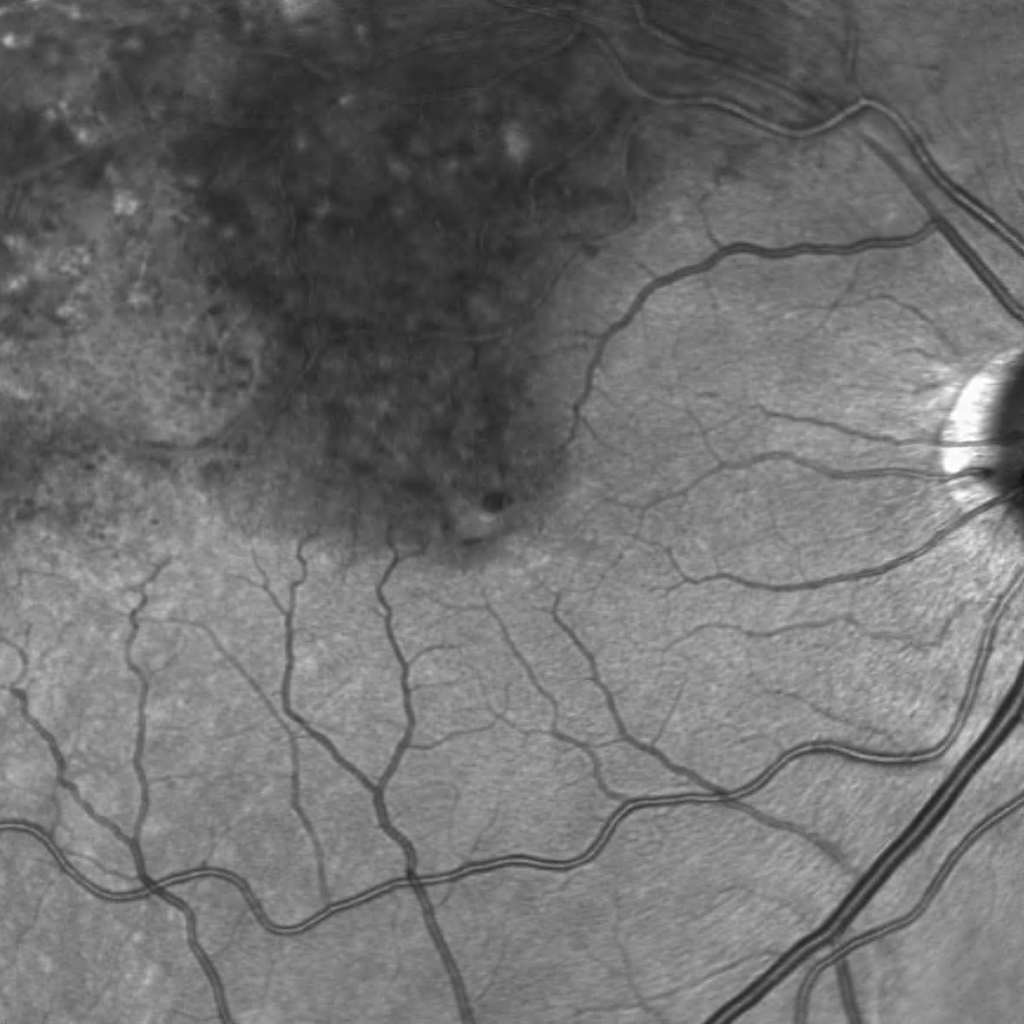

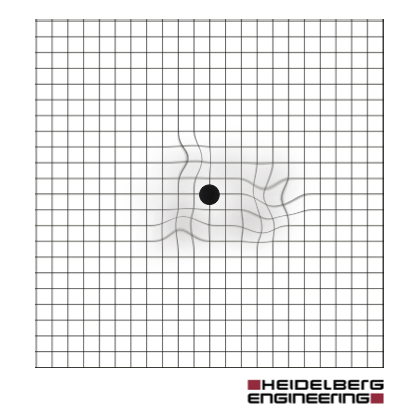

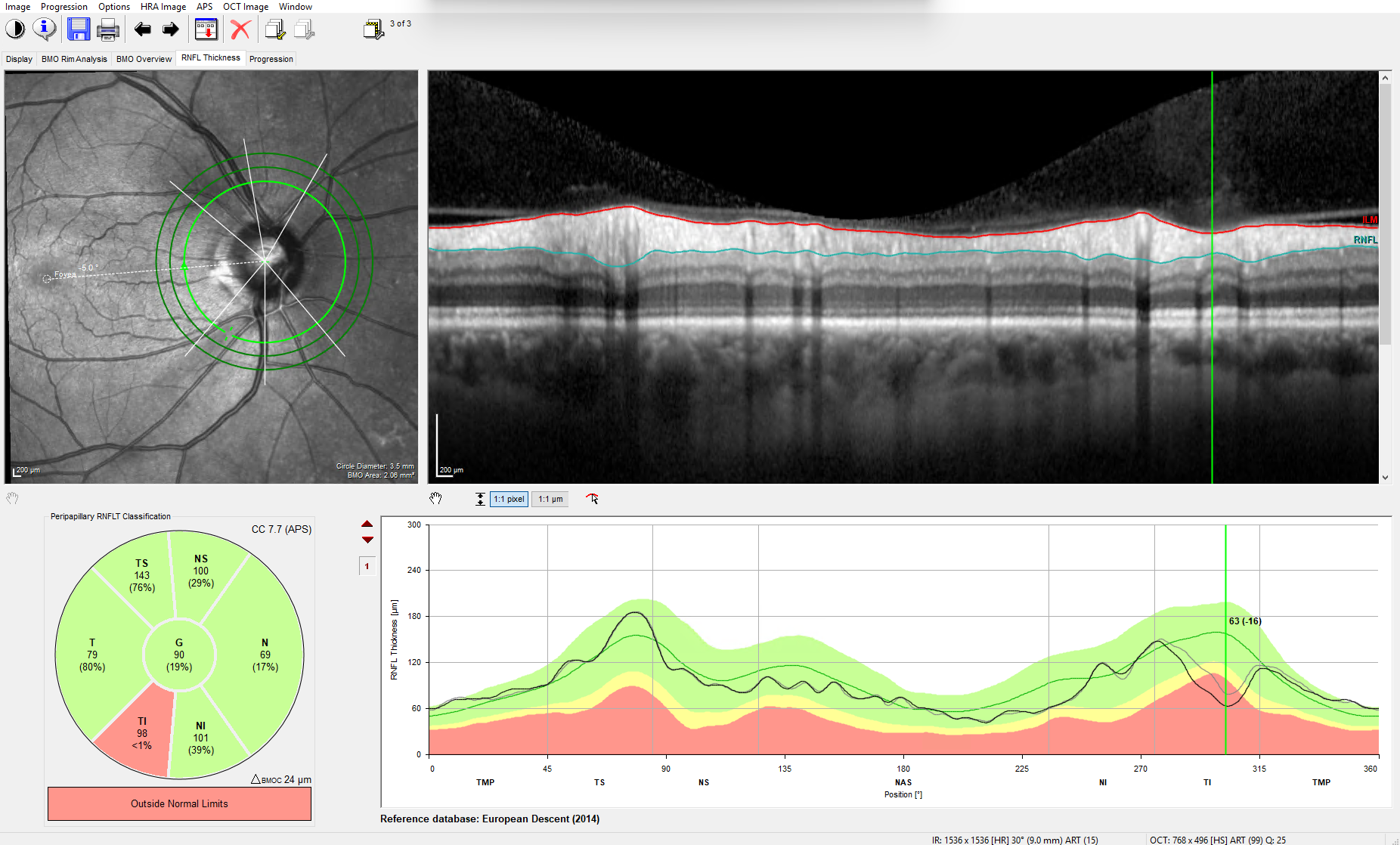

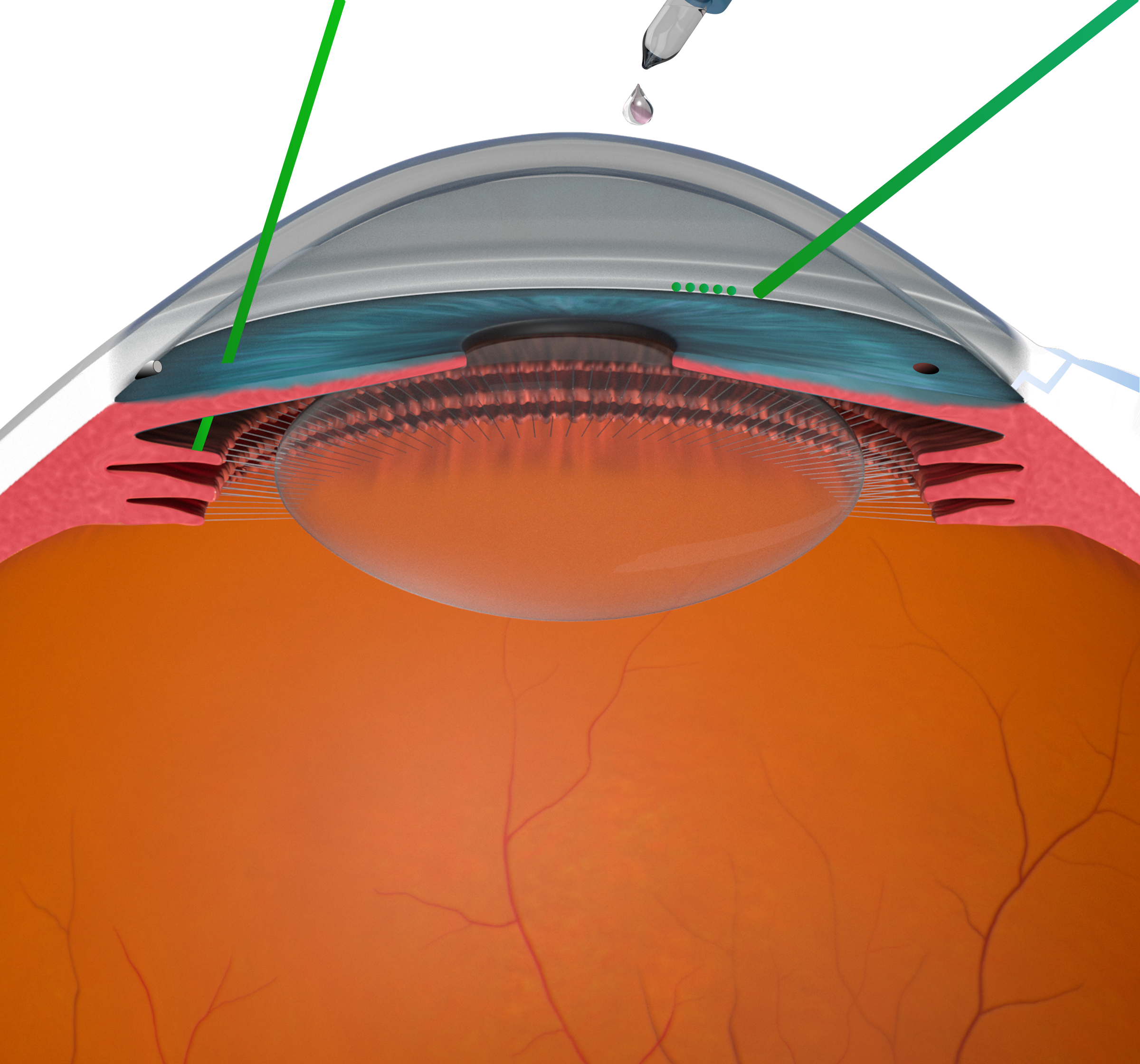

The image illustrates changes in the macula such as cystoid changes and drusen.